„JAMINI: An international arts quarterly“: Vol. 2, No. 6, November 2004

The Sculptress Baerbel Dieckmann: Classical Innovator

Etymologically, the word „sculpture“ comes from „scratch“ and „carve“; Plastik, the German equivalent, from „to mould“ or „shape“. Taking the term „carve,“ we see two aspects: to carve from some material, and to carve into some shape or form. In an act of creation, material is worked on, wrestled with, coaxed, to produce a three-dimensional work of art. John Donne in his poem, ‘A Valediction: Of Weeping,’ wrote of parts being put together to make a globe: that which was previously nothing, becomes the world, becomes everything. In sculpture, something is trans-formed into another shape, into beauty and significance. The almost instinctive and immediate appeal of sculpture to us can be traced to the pleasure we experience by seeing and touching, particularly by touching, feeling and fondling: even the blind derive pleasure from feeling sculptural works.

The expressive realist sculptress Baerbel Dieckmann was born in Bielefeld, Germany, in 1961. Attending a „grammar school,“ she was introduced at an early age to Classical literature; and its figures, stories and themes are of abiding interest to her, and strongly influence her work. The Greek and Roman gods and goddesses, in their virtues and failings, are very human: in the mythical Dieckmann sees not the distant and the strange, but the immediate and the human. On completing her school years, Baerbel Dieckmann trained, and later taught, at Art colleges. She has exhibited widely in Europe and America, and won numerous prizes. Recognised as one of the most gifted of contemporary artists, she lives in Berlin and works full time as a sculptress. Given limitations of space, I will content myself with introducing, and drawing attention to, a few elements of her work. The photographs reproduced here are all, with the exception of „die Griechin,“ by Madeleine M. Coffaro, also of Berlin. Inevitably something is lost in the process of „translating“ a solid, three-dimensional sculpture into a two-dimensional photograph, but Madeleine Coffaro has minimised the loss, accomplishing the transformation with understanding and sensitivity. I am grateful to both the sculptress and the photographer for their willing cooperation.

Much of what pretends to be modern art is affected and complicated, and incomprehensibility is mistaken by some for profound complexity. Baerbel Dieckmann has a courage born of conviction and self-confidence to beat a lonely path back to the Classics, and to works such as The Bible and its associated stories. However, this is no simplistic return but an attempt to give the past a contemporary relevance and significance: to use the past to serve a present purpose and, in that way, to keep it alive. It is a going back in order to throw some light on the contemporary. But her work is far from being derived exclusively from the Classical or the religious tradition: her subjects are equally about „ordinary“ men and women, and show the extraordinary in the seemingly commonplace and everyday. She repeatedly celebrates the „livingness“ of the human figure. In doing so, she avoids contemporary fashion and its opinion about „the body beautiful,“ and depicts also the heavy and the awkward. Significance is often sought in the simple, for example, in the beauty of a face in a moment or mood. Baerbel Dieckmann works with plaster, terracotta, bronze, stone and concrete. Again, flying in the face of fashion, her preferred media are bronze and stone. There comes to her, she says, an idea, a theme, an inspiration. Her next step is to decide on the material; thereafter, comes the building of a scaffold, and then the casting of the main form. She works outwards from this form, avoiding the danger of details taking on a life and direction of their own. Her figures, faithful to life and its truths, are often asymmetrical, uneven, rough and broken.

Much of what pretends to be modern art is affected and complicated, and incomprehensibility is mistaken by some for profound complexity. Baerbel Dieckmann has a courage born of conviction and self-confidence to beat a lonely path back to the Classics, and to works such as The Bible and its associated stories. However, this is no simplistic return but an attempt to give the past a contemporary relevance and significance: to use the past to serve a present purpose and, in that way, to keep it alive. It is a going back in order to throw some light on the contemporary. But her work is far from being derived exclusively from the Classical or the religious tradition: her subjects are equally about „ordinary“ men and women, and show the extraordinary in the seemingly commonplace and everyday. She repeatedly celebrates the „livingness“ of the human figure. In doing so, she avoids contemporary fashion and its opinion about „the body beautiful,“ and depicts also the heavy and the awkward. Significance is often sought in the simple, for example, in the beauty of a face in a moment or mood. Baerbel Dieckmann works with plaster, terracotta, bronze, stone and concrete. Again, flying in the face of fashion, her preferred media are bronze and stone. There comes to her, she says, an idea, a theme, an inspiration. Her next step is to decide on the material; thereafter, comes the building of a scaffold, and then the casting of the main form. She works outwards from this form, avoiding the danger of details taking on a life and direction of their own. Her figures, faithful to life and its truths, are often asymmetrical, uneven, rough and broken.

Art critics have noted Dieckmann’s preference for the convex over the conca ve, and though the former often makes the latter inevitable, the overriding impression is one of volume. The female figure above, full-bodied and at repose, is so living in her pensiveness — a temporary mood made „eternal“ in the sculpture – that the viewer is almost moved to protest at the sculptress „disturbing“ her with a sharp instrument. As Dieckmann has commented, sculpture lives not only from the outline and the exterior but more from what emanates from inside: one of her exhibitions was aptly titled, „the space within“ (or, „the inner space“).

ve, and though the former often makes the latter inevitable, the overriding impression is one of volume. The female figure above, full-bodied and at repose, is so living in her pensiveness — a temporary mood made „eternal“ in the sculpture – that the viewer is almost moved to protest at the sculptress „disturbing“ her with a sharp instrument. As Dieckmann has commented, sculpture lives not only from the outline and the exterior but more from what emanates from inside: one of her exhibitions was aptly titled, „the space within“ (or, „the inner space“).

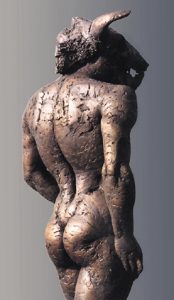

Since I have mentioned the Classics, I now move to a figure which recurs in her work, the Minotaur. The modern focus is not on Prince Hamlet but on Rosencrantz and Guildenstern (see, Tom Stoppard’s play, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead); not on the beautiful and conventionally moral Jane Eyre (the eponymous heroine of that novel) but on the mad woman, victim turned fury, imprisoned and raging in the attic: see Jean Rhys’ novel, Wide Sargossa Sea. Similarly, Baerbel Dieckmann turns not to the glorious and heroic Jason, but to the monster Jason had to outwit and kill in the Labyrinth in order to carry away the Golden Fleece.

If we view this work from its feet up, we will see a perfectly formed, muscular, male body that abruptly ends not only with the head of a bull, but a head that is skeletal: a memento mori. Few human beings are all of a piece, and it is the coexistence of contradictions within the individual that makes us complex. So too, the Minotaur is animal and man; at once both powerful and pathetic. He is not merely some mythical figure from centuries past but a metaphor of the human condition, trapped as we are in the „labyrinth“ of life. Mary Shelley in her novel describes a man-made monster who, understandably, tries to draw near to his creator, Frankenstein, but is met with abhorrence. The creature then turns to other human beings for understanding and friendship, but is met with horror, fear and physical threat. It is this rejection which makes a monster of the monster: the destructive monster that the creature becomes is the result of human prejudice, rejection and violence. The Minotaur of Baerbel Dieckmann is similar, and he stands, the quintessential outsider, lonely and misunderstood; courageous and determined; starkly strong and defiant in his loneliness; ugly and splendid.

If we view this work from its feet up, we will see a perfectly formed, muscular, male body that abruptly ends not only with the head of a bull, but a head that is skeletal: a memento mori. Few human beings are all of a piece, and it is the coexistence of contradictions within the individual that makes us complex. So too, the Minotaur is animal and man; at once both powerful and pathetic. He is not merely some mythical figure from centuries past but a metaphor of the human condition, trapped as we are in the „labyrinth“ of life. Mary Shelley in her novel describes a man-made monster who, understandably, tries to draw near to his creator, Frankenstein, but is met with abhorrence. The creature then turns to other human beings for understanding and friendship, but is met with horror, fear and physical threat. It is this rejection which makes a monster of the monster: the destructive monster that the creature becomes is the result of human prejudice, rejection and violence. The Minotaur of Baerbel Dieckmann is similar, and he stands, the quintessential outsider, lonely and misunderstood; courageous and determined; starkly strong and defiant in his loneliness; ugly and splendid.

A figure associated with the Minotaur is Dieckmann’s Cycloptaurus, a coinage from „round eyed“ plus „taurus“ or „bull.“ The creature is primeval and unkempt; strong, confrontational and menacing. And yet he comes through also as a being lost and lacking orientation, an impression created by his eyeless face, by the empty orbs that stare intently but futilely; sensing but not seeing and, not seeing, unable to comprehend. Far from being a monster, a figure of fear, it’s the creature itself who is helpless and vulnerable. This kind of opposition (here, terror and pathos, strength and vulnerability), and resulting tension is typical of Dieckmann’s work. At root, the aggression of the Cycloptaurus is an attempt at defence and, as with the Minotaur, an expression of one of the most basic of instincts, survival. The aura of terror the Cycloptaurus carries emanates not so much from him — poor, blind creature – but is imposed on him by our „gaze“ (in the Lacanian sense); by our own lack of understanding and compassion; by our assumptions, prejudices and fears about the foreign, the other. It’s we who create our monsters in science fiction, fantasies for children and, often, in real life.

It can be argued that the two major inspirational impulses behind Western art, be it sculpture, music, painting or poetry, have been religion and love. The depiction and interpretation of the crucifixion has been attempted by numerous artists over the centuries but Dieckmann’s re-presentation is wonderfully different and original. Her cross is not the traditional cross; in fact, it is not a cross but a simple wooden frame in the shape of a capital T. While most depictions of Christ crucified show him deprived of movement, here one hand has freed itself and hangs, not limp, but reaching out. If, according to Christianity, God took human form, then what we see is a human being and yet (again the paradox) God: God as man. The Christian tradition asserts that God created humankind in his likeness. If so, the converse must apply, and God has the likeness of humanity: the thought is present in the following lines, written on this sculpture and translated from the German:

The body leaning forward

still shows overwhelming power

and his hand, loosened from the cross,

blesses even as it falls:

Christ in the likeness of man.

We standing below, look up

receiving the gift of strength:

God in death creating us anew.

(Liebetraut Sarvan)

It is suffering as we human beings suffer; suffering as we human beings know it in its various manifestations and degree. (The suffering of Christ was an extreme example. Indeed, so much so the Moslem tradition holds that God, compassionate and unwilling to see his prophet treated with such cruelty, took away the soul but left the Romans in the belief that they were torturing, crucifying and killing.) A group of individuals may look at the same picture, painting or sculpture but they wouldn’t „see“, interpret and react in an identical way. In that sense, they wouldn’t be seeing the same object. As Susan Sontag observes in Regarding the Pain of Others, whatever the intention of the artist, the reaction of viewers to his or her depiction cannot be predicted, and invariably will be various. Great art is many-layered and multi-suggestive: yet another possible interpretation of this sculpture is that even as humanity needs God, God in his great love needs humanity. The arm that has freed itself reaches out in a gesture of attempted inclusion, so that the circle, most self-contained of forms, is completed. Baerbel Dieckmann, while being bold and challenging, does not set out deliberately to shock or outrage: the figures she presents, the meanings they suggest, the interpretations they challenge, never lead to a loss of respect for life. Auden’s poem, ‘Musee des Beaux Arts’ is a meditation on suffering. Of course, our own suffering is „immediate“ to us and preoccupying but even when suffering of a wider, almost universal, significance occurs, it is surrounded by the inconsequential: someone eating, others walking dully along, children playing, the dogs getting on „with their doggy life“ and the horse scratching „its innocent behind on a tree“ (Auden). In this sculpture, the momentous, the „awful,“ is balanced by the cloak or cloth indifferently thrown on one arm of the frame and hanging casually, almost as long as the hanging figure. It is as irrelevant as it is true of the casual setting of tragedy, whether great or obscure.

The story is told of Saint Martin who, coming upon a poor man on a cold day, and having nothing else to give, cuts his own cloak and hands over half to the man. In this composition, one notes the dignity of the poor man. The muscularity of his arms and legs are matched by the powerful sweep of the horse’s neck, even as the animal looks away in boredom, impatience or tact. In contrast to the empowered, dignified and demanding mendicant, St Martin looks frail. Is it the fragile tenderness of goodness and generosity in a world where these virtues are not often encountered? The beggar is on his knees; he is a supplicant, as his hands cupped to receive alms movingly testify, and yet one cannot see him as servile nor dismiss him as wretched. Critics have pointed out that by drawing a line from the head of the Saint to that of the beggar, and continuing it from the latter’s knees to the hoof of the horse, the essential integration of the composition can be made clearer. Those fortunate to view the actual sculpture will notice many other details, for example that St Martin, himself being poor, doesn’t have a saddle and that, reaching out with the cloak, he is positioned at the base of the horse’s neck: the greater exertion is on the part of the giver, though it is the need of the recipient that necessitates the gesture and the sacrifice.

This composition and others of her work, testify to Baerbel Dieckmann’s m astery of movement even when working with the most recalcitrant of material. Great sculpture is not frozen movement, is not motion arrested as in a photograph taken by a still-camera. The ancient Greeks were intrigued by the phenomenon of movement – as they were by almost every other aspect of life or phenomena – and argued that if a man or animal were to run between two points, A and B, and if time were to be divided into smaller and smaller components then, at some small fractional point in time, the person or animal will not be moving: that split second marks the stationary within movement. It is this tiny fragment of time that Baerbel Dieckmann succeeds in capturing, so that one sees not stasis but movement — the seemingly stationary is in movement, movement translated into stone or bronze. One would claim that it is the impression of the stationary that is illusory, and that the figures (all but) breathe and move: St Martin leaning forward, the raised hoof of the horse, and even the tension in the outstretched hands of the mendicant. Fluidity and motion make one resist using the word „tableau“ because it suggests a frozen, motionless, group.

astery of movement even when working with the most recalcitrant of material. Great sculpture is not frozen movement, is not motion arrested as in a photograph taken by a still-camera. The ancient Greeks were intrigued by the phenomenon of movement – as they were by almost every other aspect of life or phenomena – and argued that if a man or animal were to run between two points, A and B, and if time were to be divided into smaller and smaller components then, at some small fractional point in time, the person or animal will not be moving: that split second marks the stationary within movement. It is this tiny fragment of time that Baerbel Dieckmann succeeds in capturing, so that one sees not stasis but movement — the seemingly stationary is in movement, movement translated into stone or bronze. One would claim that it is the impression of the stationary that is illusory, and that the figures (all but) breathe and move: St Martin leaning forward, the raised hoof of the horse, and even the tension in the outstretched hands of the mendicant. Fluidity and motion make one resist using the word „tableau“ because it suggests a frozen, motionless, group.

While on the subject of motion in the apparently motionless, at one of her exhibitions, Baerbel Dieckmann had young people dance between and amongst her figures: see picture above. It was a gesture of confidence which proved well justified because the sculptures were not thereby made static: rather, the dancers became an extension in movement of Dieckmann’s figures. The young dancers among her sculptures, some of the latter representing the old; some others, the unhandsome, were reminders of the passage of time, and a joyous celebration of life. There is a striking contrast between the young dancer in the picture and the brooding monster in the background; a contrast between the yellow of the former and the sombre darkness of the latter; between the rough texture of the monster and the „sweet“ smoothness of the plaster reproduction of old classical figures. Past and present, old and young, darkness and colour, sobriety and gaiety and exuberance are all together and simultaneous – as in the world and life. To the ancient Greeks, goodness was beautiful, and that which was beautiful was beautiful because it was good. Altering these words, Keats’ Urn asserts that truth is beauty (‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’). Baerbel Dieckmann suggests that art is beauty not because it represents only the beautiful but because of its truth — and the depiction of monsters, of the misshapen, the heavy, the awkward, is „beautiful“ because of its fidelity to reality; because art seeks to depict the various seen and experienced aspects of life. One may draw a parallel with Wilfred Owen’s anti-war poem, „Dulce et Decorum Est“ which details a soldier dying in agony, the whites of his eyes rolling horribly in their sockets, and his blood „gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs.“ It is the ugliness of the poem that makes it „beautiful“ (that is, „effective“). We recognise that courage and honesty have led to the telling of a truth.

|

|

I turn now to two portraits, „Xenia“ and „die Griechin,“ (the Greek; feminine). The terracotta „Xenia“ is a face caught in abstraction, in thought. The mouth is sensuous but seems tinged with bitterness or cruelty. If the latter, does the association of passion with force, inevitably lead to an element of cruelty? Though I am aware that the model who posed for this sculpture is German, her name „Xenia“ („Xeno“ meaning „foreign“ or „strange;“ the prefix in „xenophobia“) and expression suggest alienation and loneliness: individuals can feel foreign at home. Of course, this again is a subjective reading, but it is neither possible nor desirable to eliminate the personal from an understanding of, and response to, art. On the same grounds, I would title „die Griechin“ as „Serenity“. It has been said that „innocence“ is just another word for „ignorance“ but there is another innocence which lies on the further side of experience and knowledge: the serenity in this face is not superficial but one struggled for, and achieved not because, but despite, life and experience.

The last of the sculptures I have selected is titled „die Badende“ („bathing female“) but the sculptress also suggests an alternative title: „Woman sunning herself [after a bath]“. It returns us to the first photograph, and constitutes a recapitulation of some of the features of Dieckmann’s work that we have noted. For example, the convex, full figure in a fleeting moment, awkward in its naturalness. While the body gives itself up to the pleasure of bath and sunlight, the face indicates thoughts turned inward. The visual arts make us voyeurists: admiring, we enter intimate space, intrude into a privacy that is both physical and non-physical.

The last of the sculptures I have selected is titled „die Badende“ („bathing female“) but the sculptress also suggests an alternative title: „Woman sunning herself [after a bath]“. It returns us to the first photograph, and constitutes a recapitulation of some of the features of Dieckmann’s work that we have noted. For example, the convex, full figure in a fleeting moment, awkward in its naturalness. While the body gives itself up to the pleasure of bath and sunlight, the face indicates thoughts turned inward. The visual arts make us voyeurists: admiring, we enter intimate space, intrude into a privacy that is both physical and non-physical.

Keats in the poem already mentioned (‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’) says that in the midst of transience and change, works of art remain steadfast and permanent. Art is a friend to humanity, bringing us joy and comfort (in the earlier sense of „to strengthen“): Baerbel Dieckmann’s work is yet another confirmation of this truth.

Charles Sarvan

Berlin, Germany